Remembering Cass Wheeler: American Heart Association's visionary, transformative CEO dies at 84

Cass Wheeler took over the American Heart Association at a pivotal moment.

It was 1997, and for about a half century, the organization had followed a bottom-up structure. Each of the 56 big-city and state offices did things differently. Now that structure was changing. Everything would flow out of the national office.

Although volunteers and staff were on board, many weren't happy about it. So Wheeler – recently promoted to chief executive officer – wanted to launch a project that would bring everyone together. Of course, it also had to serve the mission – preferably in a grand way.

He came up with the idea of a "breakthrough goal." Working together, Association leaders decided to aim for reducing the number of deaths from coronary heart disease and stroke by 25% by the year 2010.

That goal wasn't just met. It was met several years ahead of schedule. This meant hundreds of thousands of lives were improved and extended, and countless more people were uplifted by having their loved ones around longer. That was the kind of impact Wheeler cared about most. He also savored the fact this success was powered by teamwork across the organization.

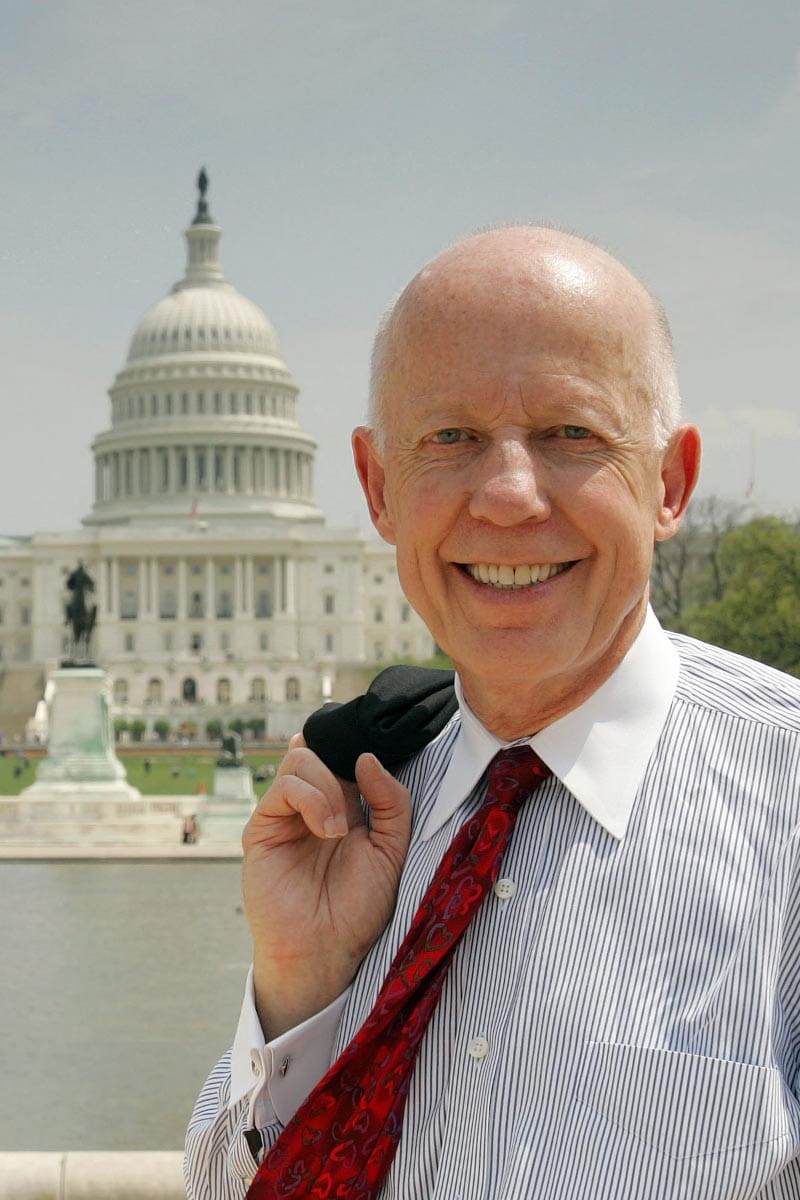

Wheeler, with a trim frame and a wide smile that lit up his face, got things done by combining a dynamic personality and a gentle touch.

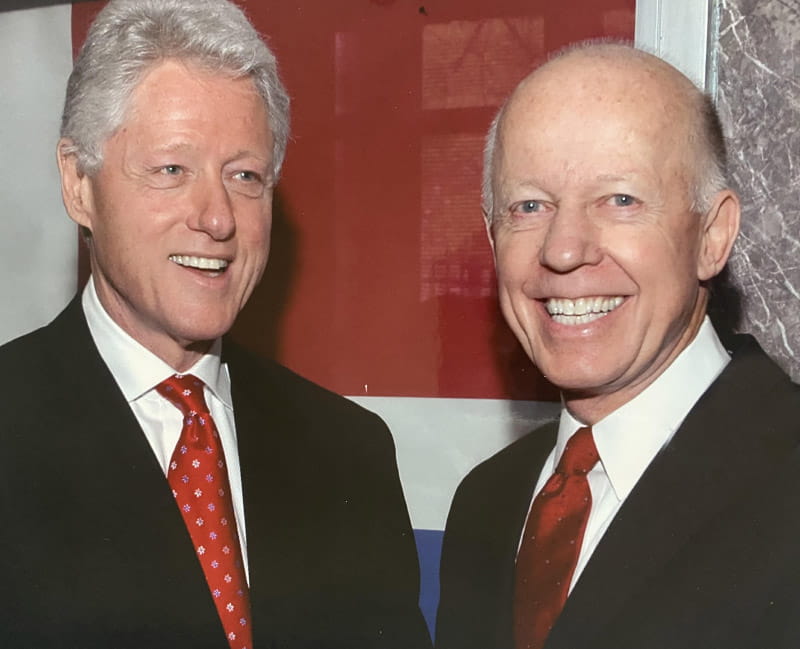

He could deliver hard truths with a twinkle in his eye. Just ask former President Bill Clinton. After Clinton underwent quadruple bypass surgery in 2004, Wheeler told him he was the "poster child for bad eating habits" and challenged him to use his setback as a teachable moment for kids. Together, they did, creating the nonprofit Alliance for a Healthier Generation.

Excellence mattered to Wheeler. He expected it. He knew how to ignite it, too. Sometimes that meant putting people in a different role. Sometimes it meant simply telling someone he believed in them. Among the future leaders he identified early and continued to nurture was his successor, current CEO Nancy Brown.

People also followed Wheeler's lead because his instincts were usually right. Like that shift to the top-down business model. He helped set it up during his rise to CEO because he believed it would make the organization more efficient and raise more money. Sure enough, over his 10 years as CEO, the depth and breadth of the American Heart Association's reach accelerated.

There's one more memorable detail that lingers in the minds of all who knew him: Every word he spoke came out in a pleasant Texas drawl.

Wheeler died June 19 in Georgetown, Texas. He was 84 and had spent much of his final year dealing with the neurodegenerative disease ALS. His daughter, Kristen Wheeler, said his final days were peaceful and filled with dozens of well-wishers who called or visited to essentially send the same message: "I love you, Cass."

"He had this magical way of instantaneously making people feel at ease," Brown said. "Relationships came first to him, yet he was always truly focused on accomplishing the mission at hand. Caring was his hallmark."

Added Clinton: "Millions of people across the U.S. are leading healthier lives today because of Cass. I'll always be grateful for the chance to work with him to start the Alliance for a Healthier Generation, which has now helped more than 31 million kids across the country get healthier food and exercise options in schools. His legacy will live on in all the people who are better off today because of his vision, skill and service."

Personal conviction to national impact

The American Heart Association is a sprawling organization. The business side exists to power programming and advocacy efforts, as well as the largest investment portfolio in cardiovascular research outside the federal government. Ultimately, it's all about saving lives. That's what Brown meant by "the mission at hand."

Wheeler showed how keenly he was focused on that during his first year as CEO.

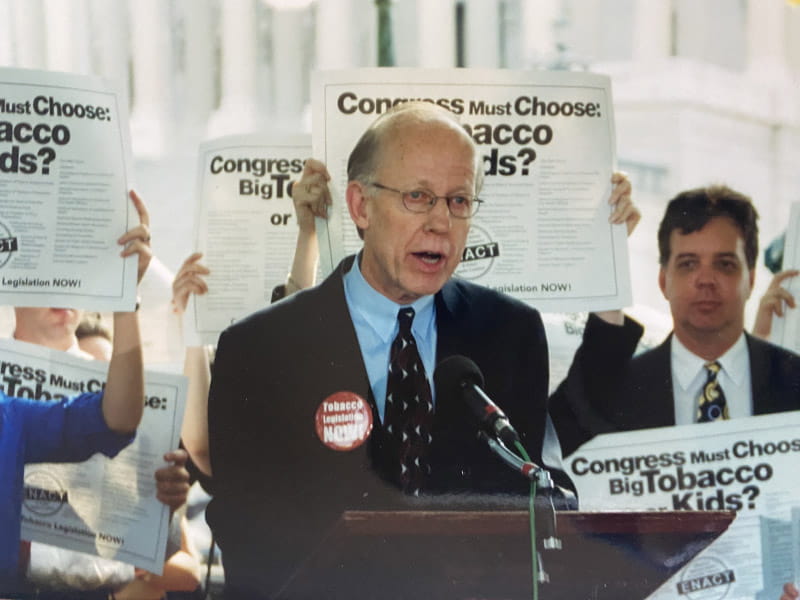

While many executives wanted Wheeler to navigate the bumpy start of the organizational shift, he hunkered down in Washington, D.C., taking part in final negotiations for what became known as the Big Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement.

His parents had been chain-smokers, and he'd smoked cigarettes, too, until learning it was a major risk factor for heart disease and stroke. By this point, Wheeler followed an extremely heart-healthy lifestyle because he thought it was important to lead by example. Getting others to quit smoking – or, better yet, not to start – made so much sense to him.

It also made sense to the American Heart Association. Ever since the landmark 1964 U.S. surgeon general's report that smoking caused health problems, generations of Association leaders had fought the tobacco industry. Now, in 1998, a deal seemed close. So Wheeler dove in.

He – and others – successfully lobbied for the agreement to include provisions the Association had long prioritized, such as banning tobacco advertising and limiting kids' access. Indeed, the settlement has been the profound game-changer many expected. Rates of smoking have been cut nearly in half. Wheeler would later call the deal "one of the top moments of my career."

Other points of pride included giving the Association's stroke division the name American Stroke Association to better emphasize the organization's commitment to brain health. He also helped launch the Go Red for Women movement to improve women's heart health, and Get With the Guidelines, which helps hospitals follow the most up-to-date standards of care and, in turn, improves outcomes for patients.

Before Wheeler even worked at the national level, he was an early champion of Jump Rope-A-Thons, a fundraising program that – in its various incarnations – has generated more than $1 billion. It's now known as the Kids Heart Challenge.

"It was never about personal glory for him," Brown said. "Cass had virtually no ego."

Wheeler spent 35 years with the American Heart Association. He previously spent six years with the American Cancer Society.

"He was able to do what he did because of the person he was," Kristen said. "Helping others is what he was wired to do."

The formative years

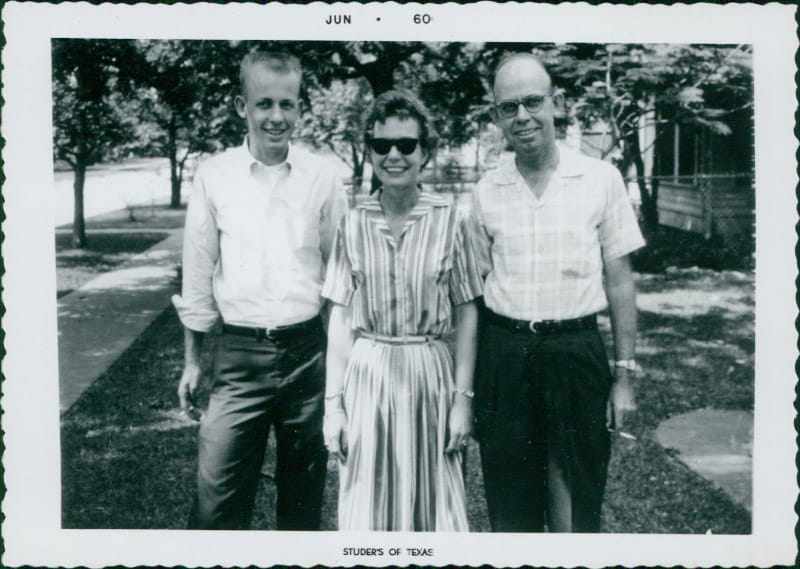

Marion Cassaday "Cass" Wheeler was born July 13, 1940, in Austin, Texas.

He grew up in Fort Worth, where his parents – known as Skip and Honey – owned an insurance company. Skip always wanted customers to have the right amount of coverage, never too much or too little. He cared about serving his customers so much that he was known to show up at a house fire while it was still burning to put an arm around his client. Honey kept the books.

Skip never graduated high school. After his dad died in a freak accident, Skip, the oldest child, had to become what his generation called "the man of the house." Still, he was a lifelong learner. He and Honey, who grew up on a ranch, were active in their church and community. They were the kind of folks who knew everyone and were the first to bring food when someone was sick or had something to celebrate.

Cass was their first child. When he was 3, his 18-month-old sister Sue Ann died in an accident. A year later, he became a big brother to Edelle. At 2 months old, she died of pneumonia. Cass never said whether the deaths of his sisters inspired his devotion to saving lives. However, in his final years, at the base of his computer monitor, he kept a picture of the headstone shared by Sue Ann and Edelle.

As a kid, Cass had his own physical challenges: clubfoot and asthma. He had overcome both by the time he attended Arlington Heights High School, where he was a grade ahead of John Deutschendorf, later known as John Denver.

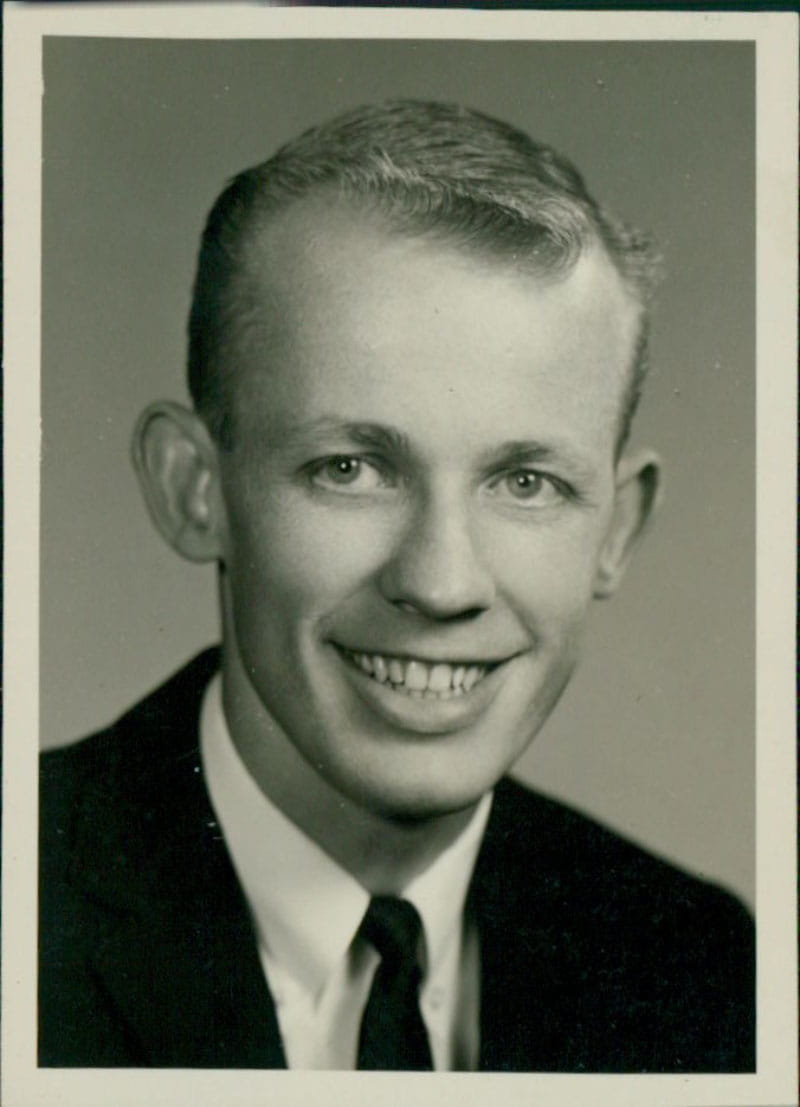

Cass Wheeler was an average student. He also got into typical teen mischief. The combination prompted a teacher to tell him, "You're never going to amount to anything." When his grades were lagging at the University of Texas, Wheeler feared he might fulfill that teacher's prophecy. He told his parents to stop wasting their money on his education.

Their response: "Stick with it. You can do it. We believe in you."

He graduated in 1963 with a business degree, majoring in advertising. Having worked part-time for the Cancer Society while in school, he landed a job in its Dallas County office. After Wheeler earned several promotions, friends encouraged him to parlay his people skills into a higher-paying job as a stockbroker. So he did – and he hated it.

Wheeler wasn't motivated by a high salary. His purpose was making a difference – and Dudley Hafner knew it.

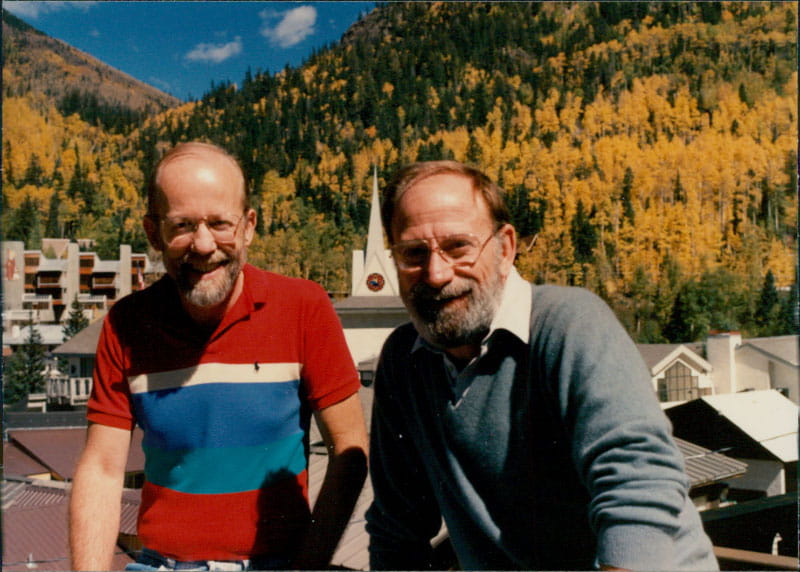

Hafner was Wheeler's uncle but, more importantly, they'd worked together at the Cancer Society. Hafner had seen that Wheeler was a doer. Now it was 1973, and Hafner was running the American Heart Association's Texas affiliate in Austin. He lured Wheeler to his team with the promise of a more fulfilling job.

Wheeler's personality, advertising background and experience in the financial world blended perfectly.

"Cass set very high standards for himself and was a very forward thinker," Hafner said. "He was generous with praise, and he wasn't afraid to take risks."

Wheeler also did a good job of learning from Hafner. So good that when Hafner moved up to the national office in Dallas, Wheeler took over the Texas affiliate.

And when Hafner became CEO, Wheeler joined him on the national leadership team.

His first job was overseeing day-to-day duties at headquarters. It was an early step toward reshaping the corporate structure.

Back then, the national team set an agenda, and each local leader executed it in their own way. This created a lack of consistency in research funding, marketing, programming and more. Hafner, Wheeler and others thought it was time for a transformational change – the organization's biggest since World War II, when the Association went from being a professional gathering to a public health agency.

It took more than a decade to revamp the system and, importantly, to get all 56 offices to cede their autonomy. Hafner shepherded the Association to that point, then retired and let Wheeler take it from there.

At least, that's how it played out.

Although Wheeler was an obvious choice to replace Hafner, the board considered 182 other candidates. He rehearsed so diligently for his interview that, nearly 30 years later, both his children remember it.

"I'm not a shoo-in," he told Kristen. "I will go up against all of them and we'll see if I'm the one selected."

A special kind of leader

Wheeler arrived at American Heart Association headquarters in Dallas in 1982. About eight years later, the Association hosted an event that brought together affiliate leaders from around the country.

During a shuttle bus ride to dinner, Wheeler made his way to a 27-year-old woman who'd recently been named executive director of the Detroit office, Nancy Brown.

She, of course, knew who he was; she was flattered he knew of her. A friendship blossomed.

"I was this young nobody, and he took a special interest in me and my career," Brown said. "And I took a special interest in learning from him."

Brown eventually became to Wheeler what Wheeler had been to Hafner: a reliable deputy, then a successor.

In October 2008, the end of his tenure overlapped with the start of hers. He insisted she move into his large, corner office. She refused. He cleared out his things early. She still waited. The friendly standoff endured as they toured the country together, Wheeler introducing Brown to stakeholders she'd yet to meet.

She finally settled into her new office around Christmas. In a coat closet, she found taped to the wall a note Wheeler had posted for himself: "Do not go up the ladder of inference!" It was one of his favorite lines, a reminder not to jump to conclusions.

"Cass was not domineering, but from time to time he could go from 0 to 100," said Brown, who kept the note hanging until the office was remodeled last year. "He could go off on something and then calm right back down."

Self-awareness became one of the many things Brown learned from Wheeler.

"He was in control, but he was never controlling," she said. "He set a great tone for the organization, one that was about external accomplishment and internal achievement."

While serving others was clearly Wheeler's calling, and he had strong leadership qualities, he also worked to sharpen them.

Kristen Wheeler half-jokingly called her dad and Hafner "leadership development geeks." She recalled them bringing in many of the giants in that field – such as Peter Drucker, Ken Blanchard, Peter Senge and Chris Argyris, creator of the "ladder of inference" – to work directly with the senior team. (Surely it's no coincidence that both of Wheeler's kids became leadership coaches.)

Wheeler also brought in Brad Smart, author of "Topgrading," a process in which everyone gets graded, with the goal of building a team of A players. Smart's task was to provide 360-degree evaluations of the Association's entire senior leadership team. "Start with me," Wheeler told Smart.

"He wanted those valuable insights to help him grow," said his son, Kevin Wheeler.

Kevin easily recited a series of his dad's favorite leadership aphorisms: "Feedback is a gift." "Dead weight won't be tolerated." "Mission before mediocrity. The mission requires us all to rise to the occasion." "Your principles and values must align. It'll be demonstrated by your productivity." "Character matters."

Kristen added one of her favorites, a tool for checking your integrity: "Never do anything you're not willing to see on the front page of The New York Times."

"Dad wasn't a whip-cracker," Kevin said. "He was always challenging people's thinking to get better results."

Added Hafner: "Cass could not, would not tolerate poor attitudes. Performance standards were agreed to and you were held to them."

At Wheeler's 80th birthday party, Marcellus Alexander Jr. told a story from when he went to work for Wheeler back in the days of the Texas affiliate.

Wheeler recommended that Alexander keep a daily diary of everything he learned. At the end of each week, they discussed what Alexander wrote in his "Cass Diaries." Alexander told everyone it made him a better learner; he went on to become president of the National Association of Broadcasters Leadership Foundation.

It's worth noting that Alexander is a Black man who Wheeler hired in the '70s, and that Brown is a woman he supported in the early '90s, because it gets to yet another element of his leadership style. He liked being surrounded by people with perspectives different than his.

"He wanted diversity in the room when conversations were being had," Kristen said, "and he always wanted to hear everyone's opinion."

A lesson in dying

Wheeler was 68 when he retired, claiming he didn't want to hang around too long and get stale.

He moved back to the Austin area and kept busy with everything from speaking about leadership to serving on boards, from hiking to cycling, from investing in a bookstore to writing the book, "You've Gotta Have Heart: Achieving Purpose Beyond Profit in the Social Sector."

Although Wheeler was recently divorced, he regularly picked up his stepchildren, Austin and Chloe Schonfeld, from school so they knew that even though he was no longer married to their mom, he was still committed to them.

He went to TEDx conferences and the Aspen Institute. He rekindled his teenage love of black sports cars and continued his lifelong love of going fast. His need for speed, so evident in his career, even manifested in his landscaping choices. When he bought a house with a barren yard in 2012, he planted a Monterrey Oak tree specifically because it grows fast.

He rooted for the Texas Longhorns, attended cultural events and supported local school board candidates. He became a regular in Boulder, Colorado, where Kristen and her husband, Paul DesRosiers, live. Cass wound up hiking so much that he was fitter in his 70s than he'd been in his 60s.

Cass often told Kristen and Kevin that he didn't want to live past 85 because he believed the quality of life dipped too far.

Nature complied, as he was in his early 80s when he contracted the rare neurological disease primary lateral sclerosis. It later became the more common ALS.

In June 2024, he was still healthy enough to travel to Chicago to celebrate the Association's 100th birthday. Brown honored him and Hafner at the main event. Hafner recalled how much he and Wheeler enjoyed reconnecting with former colleagues. Kristen was struck by how many of those colleagues said, "Cass, you've made the biggest difference in my life."

As Cass' disease progressed, Kristen, who'd become his closest companion, suggested hiring an end-of-life doula. This fit her dad's spiritual nature; for about a decade, he'd been working with a mind/body/spirit teacher.

Ever the practical leader, Cass asked Kristen to find three candidates. He and the doula he picked scripted a meaningful final few months, weeks and even hours.

Cass had always been so close to his children and stepchildren that there wasn't much left unresolved. (In a 2019 video he gave Kevin, Cass said, "They have made me a better person because one of my drivers was to always make them proud of me." In a 2020 letter to Cass, Kristen wrote, "It's no wonder that even more than one of my friends have said, 'I wish he was my dad.'")

Still, knowing time was running out, they enjoyed more special conversations. In hopes of "continuing" their conversations, he gave them, and other loved ones, a book about recognizing and interpreting signs from people who had passed.

Eventually, he began losing control of his body. ALS never claimed his spirit, though.

"He remained so loving, such a bright, shining light and so gracious," Kristen said. "In the hospital, we were laughing at the hardest things."

Two days before he died, Cass was still asking everyone in the room for their opinion before making any decisions.

On what turned out to be his final night, he was no longer able to speak. But he could listen. So Kevin spoke loving words and shared two songs purposefully chosen for this moment, both by Eric Clapton: "Tears in Heaven" and "Change the World."

Cass Wheeler is survived by son Kevin Wheeler, daughter Kristen Wheeler and son-in-law Paul DesRosiers; grandchildren Trinity Wheeler and Cash Wheeler; and stepchildren Austin Schonfeld and Chloe Barbul, and her husband Kevin Barbul. A memorial service is being planned. The family requests donations be made to the American Heart Association.