He'll be remembered as AHA's pandemic president. And his term will be fondly remembered.

By his seventh year overseeing the Duke Clinical Research Institute, Dr. Robert Harrington had grown it into the world's largest academic research organization. He felt things were running smoothly enough that he could take on another big role: a two-year stint as the top organizer for the American Heart Association's flagship meeting, Scientific Sessions.

To understand what that volunteer job entails, imagine trying to set up a Super Bowl, but with a catch. The game is one day a year; Sessions stretched over four days.

So juggling DCRI and Sessions was going to be plenty challenging. Then Stanford University School of Medicine lured Harrington west as chair of its Department of Medicine.

Harrington found a way to make everything work for everyone. Things went so well for both Stanford and the AHA that Harrington followed his Sessions role with two terms on the AHA's board of directors and a year as president-elect. Then, last summer, he became the organization's 84th president.

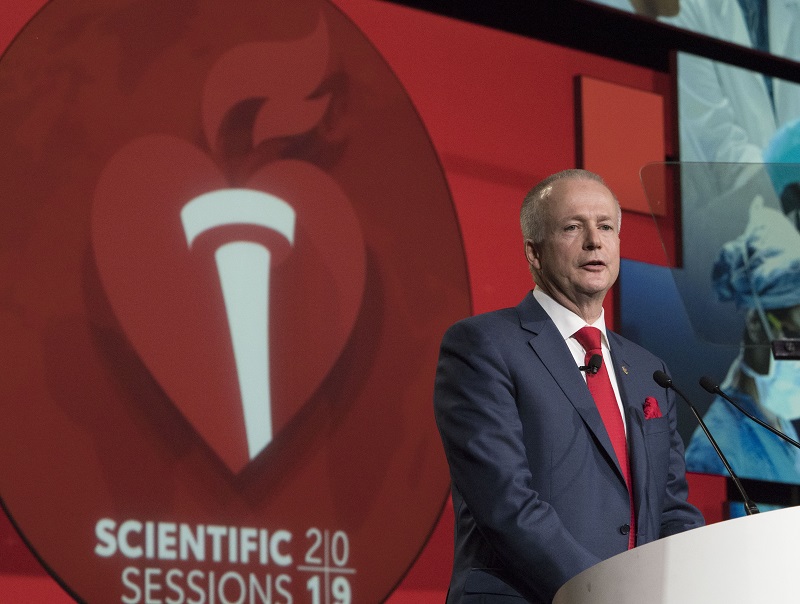

In the Presidential Address he delivered at Sessions this past November, Harrington repeatedly used the phrase "evidence matters." He linked it to every aspect of the fight against the world's top killers – heart disease and stroke.

Then came March and the coronavirus. Living in California's Bay Area – one of the first spots placed under government restrictions to limit the spread of COVID-19 – Harrington scrambled personally and professionally, including trying to deal with COVID surge planning in Stanford HealthCare, shutting down research labs and projects as campus was closed to all but essential activities, ramping up COVID-related research and helping think about the safety in the education of students, residents and fellows. At the same time, he realized that his voice would need to be a very public one as AHA put forward credible, informative and up-to-date scientific information both for the clinical community and the public at large.

Although his tenure ended July 1, his continued dedication to the AHA and strong leadership will long be remembered and appreciated. Dr. Mariell Jessup, the AHA's chief science and medical officer as well as a former president and top organizer of Sessions, likened Harrington's steady hand to Winston Churchill's gallant leadership of England during World War II.

"Bob pointed us in the right direction we needed to go, then kept us on that path," Jessup said. "He never once said, 'I can't handle that right now.'"

While circumstances may cause him to be remembered as the "pandemic president," Harrington said he hopes that when people look back on his year in charge, they'll recall "a leader who cared passionately about the science (from discovery to population health) that informs what we do as a clinical community, who cared deeply about the people who do that science and clinical care, and as someone who left the organization with some good memories."

Among those memories are two crowd-pleasing lines from his Presidential Address: "Evidence matters" and "No manels!," referencing all-male panels, something he ensured did not happen at the Sessions during his presidency.

"Those are pretty good legacy taglines!" Harrington said.

Harrington's many contributions to the organization have earned him the AHA's Distinguished National Leadership Award. He will be honored on Oct. 27 in a livestreamed ceremony.

"Over the last year, everyone involved with our organization has seen the insightful, dedicated, passionate and warm leader that I've been fortunate to work with for many years," AHA CEO Nancy Brown said. "No matter the challenge, Bob is always up for it. His spirit and drive continue to lift us."

To unravel how Harrington navigated the unprecedented challenges he faced in this role, perhaps some clues already have been revealed. The frenzied juggling of getting settled at Stanford while also planning Sessions had to help. So did his core belief in science, research, "evidence matters" and other themes emphasized in his Presidential Address, such as the importance of valuing women and immigrants, and of emphasizing health equity.

"The things he made front and center in his life and speech have turned out to be so critical through this pandemic," Jessup said. "You can't use hydroxychloroquine because it's a good idea – clinical trials have to be done. You also have to look at the impact on diverse populations or you miss the fact that Black and Hispanic people are dying disproportionately. It's all so important."

Rooted in research

Once the coronavirus turned into a pandemic, Harrington touched many parts of the AHA's response. His fingerprints are most evident on the distribution of $1.2 million in Rapid Research Grants to teams at 12 institutions for fast-tracked studies of the effects of COVID-19 on cardiovascular and cerebrovascular systems. All told, the AHA infused $2.5 million into researching how this unique coronavirus interacts with the cardiovascular and cerebrovascular systems.

Considering that the hallmark of his career involves overseeing clinical trials, Harrington was the right person for the job. Still, the circumstances were extraordinary, as was the workload. Within a month, 750 applications were culled to those dozen recipients.

"He read each one and led the discussions around which we should fund," Jessup said. "He thought strategically about including a diverse group of scientists and science topics. He recognized how important that was and he made it happen. I think this was really his shining moment."

Since growing up in a working-class part of Boston, raised by a single mom, Harrington has had a knack for shining moments.

He was on his way to becoming the first member of his family to graduate college when his mother died of a heart attack, making him the guardian of his younger sister. He considered leaving school to raise her, but relatives stepped in to help, enabling him to return to Holy Cross and earn a degree in English.

Guided by an academic advisor and an older Holy Cross grad who would become an important mentor, Harrington went on to medical school. A fascination with research, and another mentor's prediction about coming breakthroughs in cardiology, steered Harrington to Duke University for the next phase of his career.

He wound up working for Dr. Rob Califf, who was then head of the Duke Databank for Cardiovascular Diseases – and working on a clinical trial that paved the way for clot-busting medicines to treat heart attacks. That blockbuster success led to the databank being expanded from cardiovascular diseases to all areas of clinical research. It also was rebranded the Duke Clinical Research Institute. Within a few years, Harrington became head of the cardiovascular section. In 2006, Califf left to lead the overall translational and clinical science efforts at Duke, and Harrington replaced him as the director of the DCRI.

When Stanford's medical school, long known for its laboratory research, wanted to boost its clinical programs and its clinical research, the search committee targeted Harrington. Under his leadership, the departmental faculty has more than doubled, he's grown the Department of Medicine into the largest in the medical school and helped establish the Center of Population Health Sciences, the Stanford Center for Clinical Research and the Center for Digital Health.

Harrington's connection to the AHA grew during his time as a faculty member at the DCRI. Part of it was an appreciation for the organization funding so many of the institute's projects.

Having shifted into the role of Immediate Past President, Harrington remains on the board of directors and as a trusted resource for his successor, Dr. Mitch Elkind.

So, how will Harrington remember his presidency?

"I will think about how impressed I was throughout the year at how dedicated people, in both the science community and the lay public, were to the AHA mission and how consistent we constantly were with regard to what was important to the organization," he said. "It is an organization built on a foundation of science and evidence, constantly seeing the world through an equity lens."