Did you hear the one about the college student who had a stroke, then did stand-up comedy?

By Diane Daniel, American Heart Association News

Haley Warren was asleep in bed when her mother, Denise, came home from work one Friday afternoon.

A few days earlier, Haley had finished her freshman year at the University of Southern California, where she was studying screenwriting. She’d returned home to Webster, New York, near Rochester, for the summer.

Her final week of school had been chaotic. It was May 2022, and because she’d tested positive for COVID-19, the school sent her to a hotel room to quarantine. Then came finals, followed by a red-eye flight to New York. Now she was trying to adjust to the time-zone change.

“Haley, you need to get up,” Denise said, standing over her daughter.

Haley felt groggy. Her vision was blurry.

In Haley’s mind, she told her mother that she was getting out of bed and would get dressed for a relative’s birthday party.

What Denise heard were nonsensical sentences about a Halloween store and a favorite restaurant.

“Brett, get in here,” Denise called out to her husband, who was in his office one room over. “Something’s not right with Haley.”

He’d seen Haley in the kitchen around lunchtime, and she had seemed fine.

When he ran in, Haley looked at her parents blankly.

“I’m so tired,” she said, clearly this time. “I have to go to sleep.”

Denise called Haley’s pediatrician’s office. Hearing her symptoms, a nurse told Denise to take Haley, still 18, to the pediatric emergency room.

Before they left, Haley had moments of clarity. She got up to change and insisted on brushing her teeth.

At the hospital, she correctly answered doctors’ questions. Her balance was fine. But then she started making illogical remarks again.

“I know what I’m looking at,” one nurse said. “She needs to go to the stroke unit.”

A CT scan of Haley’s brain showed something amiss but was inconclusive. Because stroke was suspected – and because it was still close enough to the onset of symptoms – she was given clot-busting medication.

As Denise and nurses talked to her, Haley bounced between lucidity and incoherence.

An MRI taken later that evening showed that Haley had had a bilateral thalamic stroke. It affects both sides of the thalamus, a part of the brain that plays a role in consciousness and memory among other important functions.

Doctors also discovered a rare variation in the blood vessel structure of her brain, something known as “artery of Percheron.” That could have allowed the clot to travel. Doctors concluded that the clot itself was likely caused by Haley’s recent COVID-19 infection and the type of birth control she’d been taking.

In the ensuing days, Haley showed no problems walking or talking; she was cleared by physical therapists. But her vision was affected. When she went to use her phone, she had to bump up the text size to read the screen. To comprehend written sentences, she needed to read them a few times. She was also bothered by loud sounds and bright lights.

After three nights in the hospital, Haley returned home with instructions to start occupational therapy. She was also referred to a speech therapist to address her reading difficulties and to develop strategies that would help her when she returned to USC.

She wanted to return to her job at the amusement park she’d worked at the year before, but the lights and sounds bothered her too much. Noise-canceling headphones and dark sunglasses became must-have accessories.

Haley did get together with friends, but was often exhausted, especially after therapy sessions at a stroke rehab center. Her therapies included eye tracking exercises, matching numbers and letters and reading comprehension programs.

She was always the youngest person in the room, but that did not deter her.

“I am going back to school in the fall,” she told therapists. “So please tell me everything I need to do to get there.”

In early July, Haley felt stable enough to travel with her family to Puerto Rico for a wedding. Later that month, she started driving again.

True to her word, Haley returned to Los Angeles to start her sophomore year of school. She took a lighter course load and professors dimmed lights in class. She opted out of some script-reading exercises. Deficits in memory and reading meant it took her longer to do many tasks. She also struggled with anxiety.

In the second semester, she took an improvisational comedy class, something she’d enjoyed in high school.

It turned out that her professor had had a brain injury and the professor’s mother was a stroke survivor.

“Not only was improv great for thinking on my feet and using that muscle, I was also excited to talk to someone who understood some of my challenges,” Haley said.

Haley’s writing fluency fully returned, but her reading and comprehension continued to lag.

During her junior year, she enrolled in a standup comedy class. She turned a class assignment into a five-minute set about her stroke and recovery.

“I like to work things out through the writing part of my brain,” Haley said. “I get to talk about my struggles while also making people laugh.”

She was afraid to tell her parents because she didn’t want them – or anyone else – to think she was making light of strokes. Once she told them, they gave their blessing.

In the routine, Haley mocks her memory issues, complains that a celebrity’s minor stroke got more attention than hers and riffs about the online support group she tried, particularly the fact that most participants were at least a half century older than her.

“The first 25 minutes is teaching Barbara how to turn her camera on,” she joked.

Haley recently graduated with a bachelor’s degree in cinematic arts. She is currently assisting a TV and film writer in Los Angeles as well as working on her own screenwriting. She’s also performing in a “Rocky Horror Picture Show” shadowcast, where actors perform the action during the film.

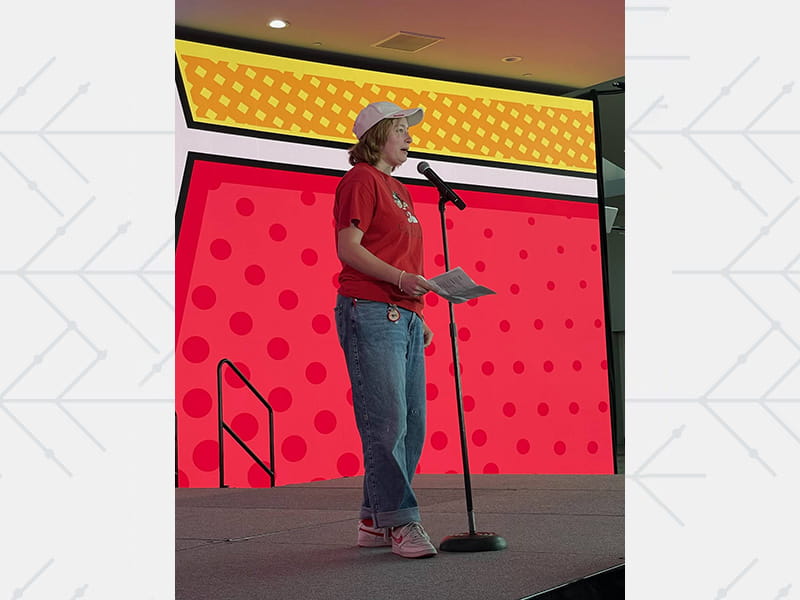

Her last stand-up show was in April at the American Academy of Neurology's annual meeting in San Diego. She took the stage after a presentation on the neurology of laughter.

The audience included about 100 neurologists, several of them being people who worked at the hospital where she was treated. They greeted her after the performance.

“It was really lovely,” Haley said.

Stories From the Heart chronicles the inspiring journeys of heart disease and stroke survivors, caregivers and advocates.

Stroke recovery is within reach. Whether it’s in person, online or on the phone, the American Stroke Association is here to support your journey to recovery. Learn more about stroke support services, including the Stroke Family Warmline (link opens in new window).