Her stroke revealed a heart defect weeks before her semester in London. Could she still go?

By Jaime Aron, American Heart Association News

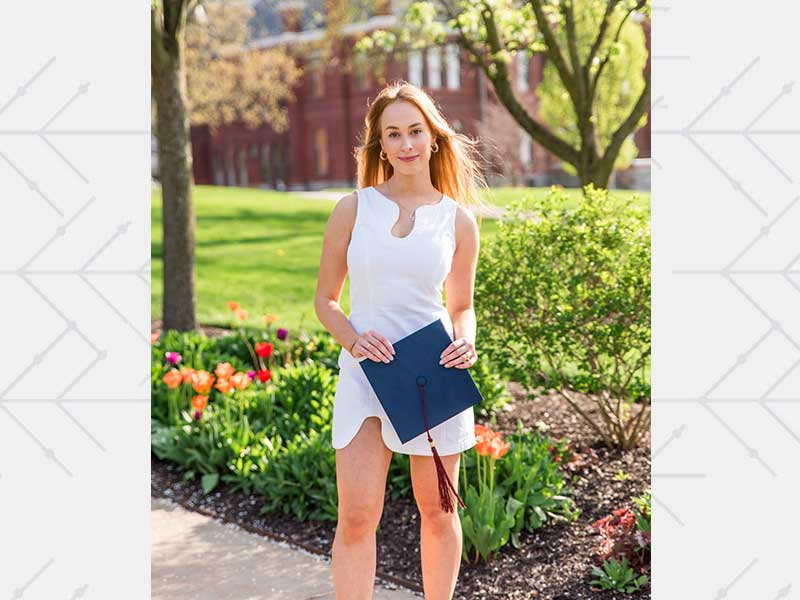

Liv Pines arrived home from the fall semester of her junior year at Syracuse University focused on one thing: getting ready to spend her spring semester in London.

Her biggest concerns were which outfits to pack and how to squeeze them into only two suitcases, both of which she still had to buy. She also was hunting for a cute winter coat.

Her best friend was going to be her roommate, so Liv – the “mom” of all her peer groups – was eager to line up restaurants and sightseeing destinations, both in London and across Europe, especially for her 21st birthday in February.

She had practical tasks to handle, too. Like getting her wisdom teeth removed. And finding an international plan for her cellphone, a must considering her status as a social media micro-influencer. For two years, sponsors had been sending her kombucha, makeup, shoes and more in exchange for posts on Instagram and TikTok.

In other words, Liv had a busy five weeks until her flight.

The wisdom teeth came out her first morning in Westport, Connecticut. The next morning, she felt good enough to go shopping. That afternoon, she played outside with her dad and Posie, her fluffy white American Eskimo Dog.

Around 5 p.m., Liv and her parents, Amy and Craig Pines, were in their den watching an episode of the documentary series "Dark Side of the '90s." A scene included a high-pitched squeal that irritated Liv, who has long been sensitive to light and sound. So she slid from the sofa to the floor to cuddle with Posie.

While kissing and petting her dog, Liv's ears began ringing. Then she felt her head pounding.

"Whoa!" she gasped, collapsing onto Posie.

Liv started to sit up – but couldn't. She felt pinned to the hardwood floor. Except for her right arm, which somehow felt like it was floating. Confused and helpless, she burst into tears.

Liv was having a stroke.

A blood clot had lodged in the back left side of her brain. It likely escaped out of a hole in her heart. Nobody knew any of this at the time. It would take almost a week to figure it out.

She would need a procedure to close the hole. And intense therapy to recover what the stroke did to the crispness of her speech and the dexterity of her right hand.

Nearly three years later, Liv is sharing her story in hopes of helping others.

She wants everyone to know that while it's unlikely that an outwardly healthy 20-year-old would have a stroke, it does happen. And she wants other women to know they may have the same risk factors she had. Because had anyone recognized these things when it mattered most, her ordeal might have played out differently.

In the moment, though, as Liv's world spun like an out-of-control merry-go-round, all she wanted was for it to stop.

When it did, she wanted to figure out what happened.

And then she wanted to know whether she could still make it to London.

Watching TV, something drastically went wrong

While Liv's parents admire her drive and precocious personality, they also know she can be a drama queen.

So when a squeal on TV left her prone on the ground, Amy and Craig both thought something like, “Here she goes again.”

Amy was the first to recognize something really was wrong.

Her first thought was that Liv fainted, knowing that she'd hardly eaten since getting her wisdom teeth out the previous day. Amy went to scoop out some gelatin as Craig helped Liv to the kitchen table.

A few bites in, Liv said, “Whoa! It's happening again!” and slumped onto the floor.

Amy called 911. Paramedics arrived quickly. The moment they lifted Liv, she vomited.

In the ambulance, paramedics asked Liv her name, birthday, phone number and address. She couldn't stop retching long enough to answer. (Her parents weren't allowed to ride in the ambulance.)

Alone in a hospital room, Liv managed to sit up straight – at least, that's what she thought. She was actually leaning about 45 degrees to the right. She stopped dry-heaving long enough to scream for help.

Doctors and nurses assumed the problem was something she ate or, considering her age, possibly ingested. Once Amy and Craig arrived, they insisted that something else was causing all this.

Liv received anti-nausea medicine through an IV. Her taste buds sensed it, making her nausea worse. The spinning lingered, at various speeds. Sometimes she felt like she was riding a plunging roller coaster; she'd squeeze the bed rails to brace herself. She always kept her eyes shut tight. Light fueled her dizziness.

She underwent two CT scans and an MRI. Liv needed help walking to and from all the machines. With every staggered step, she battled the urge to vomit.

Liv was examined by an internist and, at the family’s request, a neurologist. The neurologist said the MRI showed something on the back left side of her brain. She’d likely been born with it, he said.

The spinning, nausea and 45-degree leaning persisted for about a day and a half.

Once her head started clearing, Liv realized her right arm still felt “weak and fuzzy.” She wasn’t talking much. When she did, she slurred her words. Everyone, including her, blamed it on how drained she was.

Her only solace was being at the hospital. “They’ll figure it out,” she thought.

The search for a diagnosis

Doctors called it a severe case of vertigo or some other inner-ear disorder. They let Liv go home.

Days later, she saw an ear, nose and throat specialist. He offered exercises that could help.

That is, if the problem stemmed from inside her ear.

Amy never believed it did. Also skeptical: Dr. Richard Lipton, a neurologist who leads the Montefiore Headache Center in New York and the husband of one of Amy’s close friends.

Amy called Lipton soon after Liv reached the ER. They remained in contact as the saga unfolded. After the ENT visit, Lipton connected the family with Dr. Peter McAllister, the director of the New England Center for Neurology and Headache in nearby Stamford, Connecticut.

He saw Liv right away.

***

McAllister started the appointment by having Liv describe everything that happened.

Her speech seemed “lispy,” so he asked whether that was typical. No, her parents said.

He poked her throat on both sides. She had no gag reflex on the right side.

He asked her to hold out her left hand and tap her thumb and index finger together. She did it easily, quickly. With her right hand, she was clumsy and slow. Being right-handed, this was especially odd. She told McAllister that since the episode, her fine-motor skills were off. For instance, she could shave using her left hand, but not her right.

He asked her to close her eyes, stretch out her arms and touch her nose with her left hand. She did. With her right hand, she didn’t come close.

He had her walk in a straight line. She did fine. Then he asked her to do it with her eyes closed. She veered off course.

He had her walk heel-to-toe, like a sobriety test. She couldn’t.

The family brought a copy of the MRI. One look confirmed what McAllister suspected.

“I’m sorry to say, but you’ve had a stroke,” he told Liv.

He pointed to a spot on the image – that same one the hospital neurologist said she was probably born with.

“This is one of the most obvious examples of a stroke that I’ve ever seen,” McAllister said.

McAllister explained more clues hidden in plain sight.

Liv has a history of migraine with aura – headaches with visual and sensory disturbances, such as flashes of light, tingling sensations and difficulty speaking.

It started in grade school. At this point, she routinely had six to eight moderate headaches per month. Several times a year, she had migraine with aura that lasted about half an hour.

Also, for the past two years, she’d been taking oral contraceptive pills containing estrogen. Such pills are safe for most people – except those with a history of migraine with aura.

When someone with a history of migraine with aura takes estrogen, they’re at a higher risk for blood clots. Blood clots cause the majority of strokes.

McAllister also recommended that Liv get an echocardiogram, which is an ultrasound of her heart.

He believed Liv’s heart had a hole in it, a condition called a patent foramen ovale, or PFO. Everyone is born with it. Nature usually resolves it. However, as many as 1 in 4 don’t close. In those cases, blood clots can flow from one upper chamber of the heart to the other, without getting filtered out by the lungs, then out to the rest of the body.

Because PFOs are so common, and often cause no problems, they’re not worth screening for. Until someone has a problem that might trace to it.

Like a stroke.

***

Liv walked out of McAllister’s office and began bawling.

This was the new low point in her ordeal, worse than the violent spinning and retching.

No matter how awful she felt during those 36 hours, she knew that episode would eventually end. When it did, she considered it over with, like a severe bout of food poisoning.

Now, this would forever be part of her life story.

“I’m a stroke survivor,” she thought. “And I might have a heart problem?!”

But McAllister had also given Liv something else to think about.

He wanted her to return to the clinic the next day to start therapy. An hour a day of physical therapy, occupational therapy and speech therapy. Not an hour total; an hour of each. Five days a week, for three weeks.

After all, she had a plane to catch.

That’s right. He believed she could still make it to London.

‘You’re better than new’

An echocardiogram not only showed that Liv had a PFO, it revealed what McAllister described as a large one. A few days later, she underwent a relatively simple outpatient procedure to close the hole.

Genetic testing showed no other likely stroke risk factors. That meant all signs pointed to McAllister’s hypothesis as being correct: The combination of Liv’s history of migraine with aura plus estrogen contraceptives probably caused a clot that escaped through her PFO and lodged in her brain stem.

Since leaving McAllister’s office, Liv had stopped taking the estrogen pills. She still had a history of migraine with aura, but the PFO closure might help with that. (Her cardiologist, Dr. Robert Sommer of Columbia University, is a lead researcher on a clinical studyevaluating whether closing PFOs with the umbrella-type device she received relieves migraine. Lipton, the neurologist who is a family friend, also has studied the possible link between PFO and migraine.)

Put it all together and …

“You’re not as good as new – you’re better than new,” Craig told Liv. “You’re healthier than you’ve ever been in your entire life.”

***

From the start of all this, Amy and Craig took lots of pictures.

They knew Liv would want everything documented. She did.

The day of her PFO closure, Liv used 19 of those images in a TikTok post titled, “My winter break in a nutshell.”

Before hitting publish, she wondered whether anyone would care enough to watch.

The post racked up over 170,000 views and over 100 comments. Her favorites were people thanking her for the heads up about the dangers of taking estrogen if you have migraine with aura and for showing that stroke isn’t something that only happens to the elderly.

***

Liv’s post ends with her looking up and away, flashing two peace signs and an overlay of the words: “And now it’s time for London.”

McAllister and Sommer were good with her travel. Each connected Liv with a specialist in London. Liv started wearing a smartwatch that monitored her heart. Because of all that, Amy reluctantly gave her blessing, half-jokingly calling herself, “Mother of the year.”

Liv left a mere week later than planned. Everything went great. She soaked up the fun, food and fashion, plus an unforgettable 21st birthday in Paris.

She’s since graduated from Syracuse, moved to New York and, now 23, works in marketing and social media.

To anyone meeting Liv for the first time, her speech seems fine. Family and friends, however, can detect an occasional lisp. Certain words come out differently now, especially when she’s tired. Her right hand remains compromised. Writing is her biggest challenge.

“Even something as simple as a thank-you note gives my hand this fuzzy feeling, like of exhaustion,” she said.

Since the PFO closure, Liv has “totally, totally, totally” noticed a difference in her headaches. They occur less often and they’re less intense. She’s had just a couple of migraines, only one with aura.

A cautionary tale for other women

One of the threads woven through this tale is all that went wrong before Liv got the right diagnosis.

If only someone – a doctor, pharmacist, friend, anyone – had mentioned that people who have migraine with aura should discuss with their doctors the risks of taking estrogen, Liv may never have had a stroke.

If anyone who responded to her emergency had realized she had those factors and thus an elevated stroke risk, perhaps someone would’ve detected the clot sooner. Had anyone detected it within 4.5 hours of her collapse, she could’ve received clot-busting medicine that might’ve preserved her speech and use of her right hand.

If anyone had realized that people who have vertigo don’t also have weakness on one side and speech difficulty, and if they’d remembered that those are warning signs of stroke, maybe she could’ve begun therapy sooner.

“It was not all that complicated of a diagnosis. You just had to recognize the subtle signs,” McAllister said. “Being a woman and being young are risk factors for not being taken seriously enough.”

Then there was the misread MRI. Mistakes happen. But consider this: For several years, when McAllister wanted to show anyone a textbook example of what a stroke looked like, he showed them an image of Liv’s MRI that he kept on his phone.

As for the fact Liv had her wisdom teeth removed the day before the stroke, all signs point to it being a coincidence.

Maybe something about the procedure – such as inflammation or a side effect of the anesthesia – served as a tipping point. But it’s impossible to verify. The question fascinates her periodontist. He told the family Liv is his first patient to have anything like this happen so soon after a procedure.

***

The final layer of Liv’s story is gratitude.

If she had to have a stroke, and one that revealed a congenital heart defect, she’s thankful it happened at home, with her parents by her side. She’s thankful she had access to skilled doctors such as Lipton, McAllister and Sommer.

She’s thankful it happened so early in her life. She’s even thankful the London trip gave her a deadline to inspire a speedy recovery.

“What if it had happened in my dorm at Syracuse?” she said. “Or while I was on the dance floor of a frat party? Or while I was in London? Would I still be alive?”

Gratitude prompted the TikTok post in which she first shared her story. More recently, it prompted an email to the American Heart Association in hopes of further sharing her story.

The Venn diagram of people she’s trying to reach includes circles for everyone considered too young to have a stroke: women 45 and under who have migraine with aura, women 45 and under who have migraine with aura and take estrogen, and women 45 and under who have migraine with aura and take estrogen and have a PFO.

Each circle gets smaller, of course.

But plenty of people fall into these groups. McAllister noted that three months after treating Liv, he treated another 20-year-old college student with the same risk factors who also had a stroke.

So, they’re out there. And, Liv hopes, they or their loved ones are reading this.

Stories From the Heart chronicles the inspiring journeys of heart disease and stroke survivors, caregivers and advocates.