Heart health research of 9/11 survivors slowly realized, 17 years later

By American Heart Association News

Back when Charlie Wilson was an avid runner, the only flutter he ever felt in his chest came from indigestion.

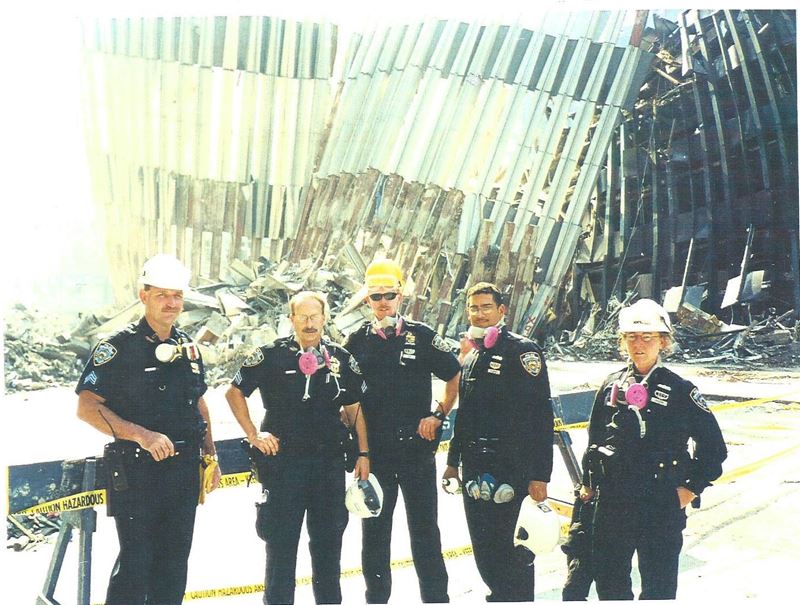

That changed on Sept. 11. The now-retired New York police sergeant spent nearly every day for the next six months at the World Trade Center. He helped with rescue and cleanup missions, all while breathing in the hazardous dust still settling over lower Manhattan.

The work soon left Wilson with horrible sinus problems. Years later, he developed sleep apnea and asthma. And on Oct. 19, 2011, Wilson received a pacemaker after years of dealing with an irregular heartbeat.

Wilson, 59, is among thousands of first responders, volunteers and New York residents with ailments and diseases linked to 9/11. More than 71,800 first responders and 16,600 survivors currently receive treatment through the World Trade Center Health Program.

Yet 17 years after the world’s deadliest terrorist attack, research has only started to uncover ways in which the aftermath has literally altered the hearts and minds of those affected.

Respiratory illnesses were among the first widely reported health issues, usually characterized by chronic coughing and wheezing. Acid reflux was another common complaint, along with sleep apnea and sinus problems that often led to blocked upper airways.

Many of the problems were linked to the fact that the collapse of the twin towers filled the air with numerous carcinogenic particles and chemicals, including asbestos and fiberglass, exposing anyone within reach of the colossal cloud.

Only more recently has research shown a link between the dust and cardiovascular health.

A study published last year in the journal Environment International(link opens in new window) found that New York children exposed to the dust because of where they lived in the wake of 9/11 may be at higher risk for heart disease. Blood tests of teens and young adults who were children when the twin towers fell showed high levels of artery-clogging cholesterol.

Another study published this summer in the journal Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes(link opens in new window) showed a link between cardiovascular health and post-traumatic stress disorder, a common illness among 9/11 rescuers, volunteers and survivors. The research found that response crew workers who suffered from PTSD had more than double the risk for heart attacks or strokes than those without the disorder.

Dr. Alfredo Morabia, the study’s lead author, noted that heart disease is not formally recognized as a World Trade Center-related condition, but substantial research has demonstrated the need for medical insurers to consider the connection as such.“I think the evidence is very strong,” said Morabia, a professor of epidemiology at both New York’s Columbia University and the City University of New York.

Dr. Aaron Pinkhasov, a clinical professor of psychiatry at New York University School of Medicine, said he is not surprised to see research linking PTSD with cardiovascular health.

PTSD affects the part of the brain that responds to fear, and the brain can overreact to even benign situations. This disrupts the immune system and triggers an inflammatory response known to harden arteries. It also affects social behavior, sometimes leading to a withdrawn, sedentary lifestyle and poor dietary choices that can elevate stroke and heart attack risk, he said.

Other studies published this year in JAMA Oncology found that World Trade Center firefighters have a heightened risk(link opens in new window) of developing a type of blood cancer called multiple myeloma. It is expected that they also have a greater chance(link opens in new window) of being diagnosed with prostate cancer, thyroid cancer and melanoma in years to come.

On Sept. 11, 2001, Wilson was a NYPD sergeant helping set up polls for a primary election when the first plane crashed into the World Trade Center. He immediately headed downtown and began evacuating people from the area.

When the second tower collapsed, “it was like a wave just picked me up, like body surfing,” Wilson recalled. “It picked me up and threw me over the top of (a) van.”

Wilson ended up breaking his back, but continued working until 3 a.m. the next morning.

In an Injury Epidemiology(link opens in new window) study last year, people like Wilson who sustained significant injuries on 9/11 were twice as likely to develop heart disease as people who didn’t.

Wilson’s back injuries eventually prompted him to retire from the police department in 2005. Other health problems followed, including the heart flutter that doctors failed to diagnose for years until shortly before he got his pacemaker. The device picked up another heart condition called atrial fibrillation.

His heart problems have not officially been tied to 9/11, he said.

“With all the research they’re doing now, it will happen,” he said. “It’s going to come out eventually, but I don’t know if I’ll be around to see it.”

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email [email protected].