He pushed for pulse ox screening. Then his grandson’s pulse ox level was dangerously low.

By Nancy Brown, American Heart Association CEO

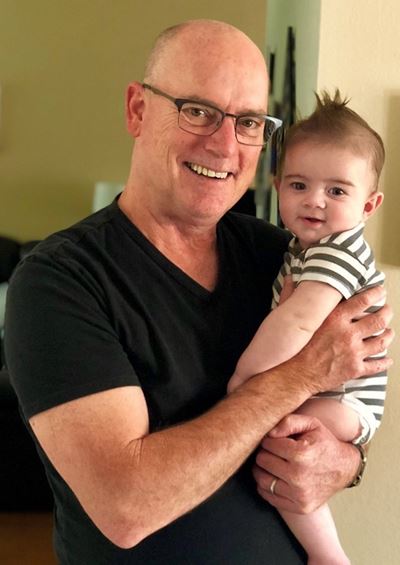

Bob Larlee needed help. His 3-week-old grandson Chase was in a hospital room, hooked up to all sorts of machines while doctors tried figuring out what was wrong with his heart.

So Larlee called one of the best heart doctors he knew, Tom Pfeffer.

Pfeffer is a surgeon at Kaiser Permanente’s Los Angeles Medical Center. From 2004-13, he was chief of the hospital’s cardiac surgery department. During that time, he also was a volunteer leader of the Los Angeles chapter of my organization, the American Heart Association. Larlee was a volunteer leader at that time, too. Now, with Chase at Pfeffer’s hospital, it only made sense to seek his friend’s insights.

Larlee started by telling Pfeffer everything he knew. Pfeffer gathered some information on his end, then called Larlee back. Pfeffer was going over what his family probably would be facing when he put Larlee on hold.

One of Chase’s doctors was calling with test results.

Minutes later, Pfeffer returned and said, “I’m sorry to tell you this, Bob, but Chase needs open-heart surgery.”

Larlee broke into tears. This sweet, beautiful boy he’d fallen in love with was fighting for his life.

Then Larlee flashed back to his time working with Pfeffer and the AHA. He recalled galas featuring people who’d overcome worse diagnoses. He remembered lunch meetings where scientists explained research breakthroughs and emerging technologies.

“This,” he thought, “is what that was all about.”

***

Larlee’s path to the AHA started with, of all things, a game of Monopoly.

In 2004, a friend and AHA board member, was organizing a black-tie fundraiser for the AHA based on the board game. Instead of Boardwalk and Park Place, properties were named for real estate companies participating in the event. Event signs and graphic materials were made and donated from the landscape architecture firm where Larlee was a partner.

Larlee was invited to attend. He wound up matching wits in the pretend real estate contest against stars of the real-life version.

Larlee won. Two years later, he won the game again.

Larlee also enjoyed learning about the AHA. He already felt a connection to the mission; his dad died following a series of strokes and his grandfather died of a heart attack. Both were in their 60s at the time, a fact that loomed larger every birthday.

“I decided that I wanted to do more,” he said.

Larlee joined the local board of directors in 2007, eventually becoming chairman.

That year was not a great time for taking over a volunteer post with a heavy emphasis on fundraising: It was the beginning of the great recession, a challenging time for all Americans, including the nonprofit world.

Larlee spent five years on the board, half as chairman-elect or chairman. He visited Washington, D.C., twice to encourage federal lawmakers to support AHA aims, and he made several trips to the state capitol in Sacramento to lobby state lawmakers.

At the time, we were among the organizations pushing for a state law requiring newborns to undergo pulse oximetry screening before they leave the hospital. It’s an easy, inexpensive test to determine the amount of oxygen in the bloodstream. A low percentage can be a sign of a congenital heart defect. Catching it early can reduce the chances of death or disability.

“I absolutely bought in on the need for this,” Larlee said. “The government has a role and shares a responsibility to create a healthier environment for us to live in. The pulse ox legislation has great implications because it saves lives and saves later costs.”

***

Around the same time the pulse ox screening became a law, Larlee left the AHA board. It was among many transitions in his life.

He got divorced and changed jobs. He fell in love again and remarried. His sister, an ordained minister, performed the ceremony. She later performed the wedding ceremonies of his wife’s two daughters from a previous marriage. (He also has a teenage daughter and son from his first marriage.)

Larlee has become close to his stepdaughters Vanessa and Sarah. Vanessa now drops the “step” when introducing Larlee.

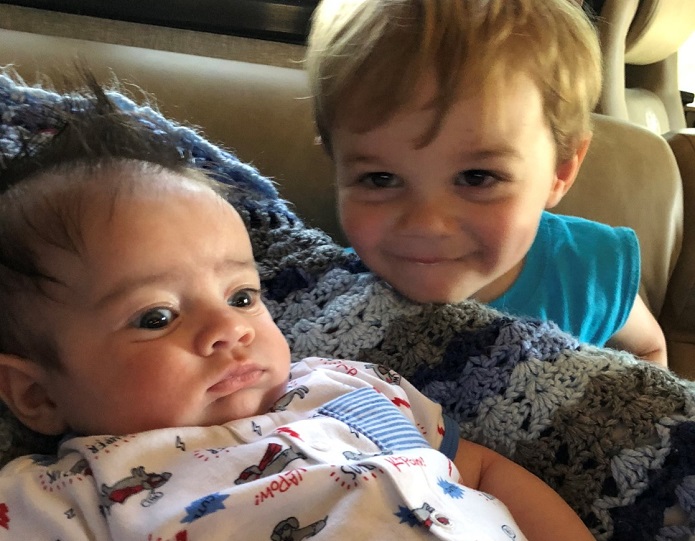

In 2015, Vanessa had a son named Cole. He calls Larlee “Papa.”

In March, Cole became big brother to Chase.

***

Chase was born about three weeks early. After a few days in the neonatal intensive care unit, he was deemed healthy enough to go home.

Days later, his skin color seemed a little off and his breathing was a bit heavy. Everyone attributed it to his early arrival, before his lungs were fully developed. Everything else seemed normal.

During a routine wellness check with a pediatrician, a pulse ox screening device was clipped to Chase’s foot. It showed that his oxygen saturation level, which should’ve been in the high 90s, was in the 80s.

Chase went by ambulance to a nearby hospital in his suburb 40 miles north of Los Angeles. That night, a specially trained team transported him to Kaiser Sunset in Hollywood, where Pfeffer works.

The next morning, while Larlee was on hold, Pfeffer received the news that Chase was born with a rare condition called total anomalous pulmonary venous return, or TAPVR. Essentially, the veins that connect the lungs to the heart were in the wrong place. Fixing it required going in and rearranging the veins.

The open-heart surgery was on a Friday. Because of swelling, the chest cavity was left open until Sunday.

“The following Friday he was being laid gently on our coffee table for his diaper change,” Larlee said. “That’s remarkable. That’s all because of research.”

***

During another checkup in July, doctors discovered that one of Chase’s relocated veins was completely blocked. Upon further testing, Chase was diagnosed with an abnormal thickening called pulmonary vein stenosis.

Doctors considered going back into his heart, but because Chase’s vital signs were somewhat normal, they thought it was possible his body adapted and found a new way to get blood into his heart. This detour around the blocked vein is known as a collateral vein, and further tests showed that’s exactly what happened.

Doctors will continue monitoring this and another congenital heart defect he has, a hole between the left and right sides of his heart. This is called patent foramen ovale, or PFO, and about 25 percent of people have it. The hole can be left open as long as it’s not causing problems.

***

As things played out with Chase, his mom wanted to become involved with the AHA.

Larlee called the local office to introduce her. One thing led to another and now he’s back on the LA board.

“It felt really good being involved the first time,” said Larlee, who was named the 2011 Advocacy Volunteer of the Year for our Western States Affiliate and who in 2012 was the top individual fundraiser in the LA County Heart Walk.

“But now that I have a grandson in the throes of a heart problem, I’m not a spectator anymore,” he said. “I’m one of the families going through this. … I’m going to do everything I can to turn the love I have for Chase into giving back. That’s my goal. It’s a journey we’re on together.”

A version of this column also appeared on Thrive Global.

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email [email protected].