Grief is never easy, but military families can bear added burdens

By Michael Merschel, American Heart Association News

The death of a loved one is never easy. But survivors who've lost someone in the armed services experience it in ways others do not.

"Military grief is experienced publicly and also very personally," said Bonnie Carroll, president and founder of the nonprofit group Tragedy Assistance Program for Survivors, or TAPS.

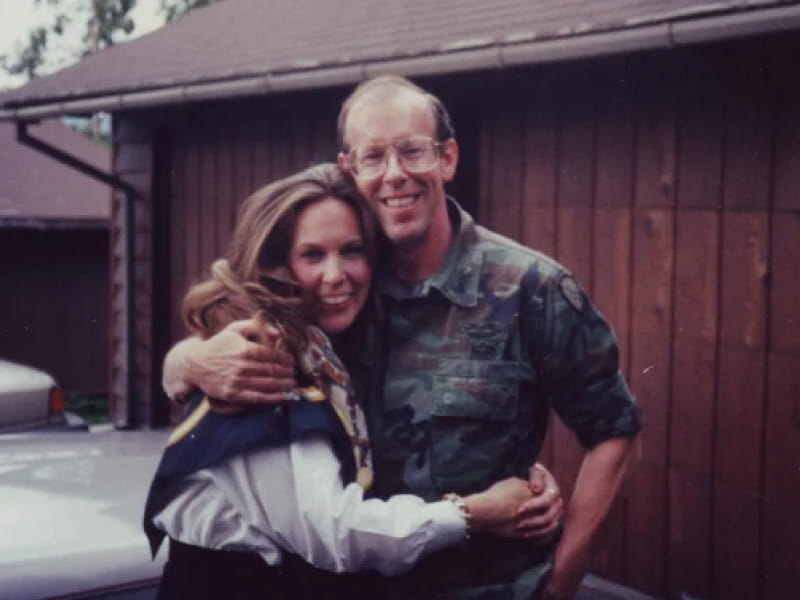

"For families, there is a tremendous amount of tradition and honor around the military loss," from how survivors are informed of a death to how they are presented the folded flag at the funeral, said Carroll, whose husband, Brig. Gen. Tom Carroll, died in an Army plane crash in Alaska along with seven other soldiers in 1992.

"We have words that we use: 'gave one's life in service to one's country,' or 'made the ultimate sacrifice,'" said Carroll. And there are special days – such as Memorial Day – that bring such feelings front and center.

It adds complexity to the already-tangled grief process, experts say.

"People tend to think of grief as sadness or depression, but it really is different," said Dr. Stephen Cozza, a professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at Uniformed Services University in Bethesda, Maryland.

Cozza, a retired Army colonel who has done extensive research on bereavement among military families, said that when we lose a person who is close to us, the essential way we think, feel and engage the world all gets ripped out of us.

"It's like part of us is also lost," he said.

He called grief an "emotional, cognitive and biological response" to bereavement. Cognitively, it can lead people to become scattered and confused. Biologically, grief may lead to immunological changes and cardiovascular issues, including raising the risk of heart attack and stroke.

Emotionally, "it can be very messy," said Dr. Meredith Charney, a licensed clinical psychologist in Portland, Maine, who has studied grief. It can include yearning and longing, emotional pain and withdrawal from others, said Charney, who works both with MaineHealth and Psychology Specialists of Maine. She described grief as "the form that love takes when someone we love dies."

What's unique about military grief

In the military, Cozza said, deaths are usually "sudden, unexpected and very often can also involve some kind of violence." That includes people who died because of combat, accidents or suicide, the latter of which affects veterans at higher levels than the general population.

Unexpected deaths tend to provoke more challenging grief responses, Cozza said, "largely because people are just unprepared for them." The suddenness can lead to "a profound sense of disbelief" or feelings of being disoriented or disconnected from the world.

Military deaths often involve a young person, Cozza said. "So that can feel unnatural in that those deaths are untimely and unexpected."

Most military deaths involve men, Cozza said, so survivors often are young widows and children. They commonly are living on military installations far from extended family members they could lean on for support. Similarly, parents of someone who died in the military are likely to be far from the place where their child died.

The nature of military life can add to the shock, said Carroll, a veteran of the Air National Guard and Air Force Reserve. A spouse might go from enjoying being the partner of a high-ranking commanding officer to having to vacate their home on a military base to make room for the next occupant. A child might be issued a new military ID card that changes their very identity from "active duty" to "survivor."

Surrounded by ceremony

The ceremonial aspect of a military death can be a source of support or an additional burden, depending on the survivor's attitude, Charney said. "It is possible that someone could find solace in not grieving alone, that other people care." Others might want more privacy and feel "they didn't necessarily ask for this kind of attention."

News of a death may come in the form of a knock on the door and not a call from a hospital, Carroll said. "That moment of notification is, for the family, a trauma memory."

Pride and pain can overlap, she said. "The public may see a military hero. The family grieves a whole human being with dreams and laughter and love. And the intersection of public recognition and private heartbreak creates this complex emotional reality."

Even the nature of a holiday meant to honor their loved ones, such as Memorial Day, can stir emotions, in the same way Mother's Day might affect someone who has lost a mother or an anniversary would affect someone grieving a spouse, Charney said.

But, she said, while loss can be "so painful," it's important for the bereaved to know that many things can help, and even in the depths of grief, "there's a lot of reasons to still feel hopeful."

Taking care of the bereaved

For those not directly affected, reaching out to support survivors is important, grief experts say.

"Sometimes people have a hard time asking for help," Charney said. "So if you haven't heard from that person, it doesn't mean they don't need you." Memorial Day might be an especially good time to say, "I'm thinking of you, I'm thinking of your loved one, and you're not alone."

Practical aid – such as bringing food or offering to drive children around – "can be tremendously helpful," Cozza said. For a grieving person, it can be vital to know "that you have other people in your life that are coming to assist you, to be with you, to mourn with you."

As time goes by, acquaintances can back away from the bereaved, but families may need continued support for an extended period, he said. Well-meaning friends might be afraid to discuss a loss for fear of stirring up sadness, but Cozza said they should remember that for the grieving, the sense of loss doesn't go away, even after it decreases in intensity. "In the first days and months after the death, it's the first thing that they think about in the morning. They may think about it all day."

Friends should say the name of the person who died, he said. "It can be helpful to share a loving memory" of how that person affected you. Such remembrances keep the person's memory alive "in ways that I think are important," Cozza said.

Avoid dictating to a person how they should feel, using cliches about why bad things happen, explaining things to them in ways that worsen their pain, or telling them they need to "move on."

Support needs to be done in a sensitive way that addresses what the survivors truly want, Cozza said, so don't make assumptions about their needs. Instead, ask them what they would like.

The mix of emotions will vary by circumstance and individual, he said. Survivors of someone who died by suicide might be focused on what they feel they could have done to prevent the death. A combat death might give a sense of pride at their loved one's sacrifice – or anger at a leadership decision that sent them into harm's way.

Attitudes and needs can differ even within a family. A parent who encouraged their child to serve might end up in conflict with one who was opposed to that service, Cozza said.

Survivors can help themselves by being patient with the process, Cozza said. He encourages people "to both allow themselves to be in grief while finding ways to take breaks from it." That means giving yourself permission to step away from it when you're able, with the understanding that you'll also need to engage with the pain when it shows up. "Grief has its own rhythm and can suddenly and powerfully affect us. Sometimes it just comes and lands on you without warning."

Grief-specific treatments can help, as does seeking support from others, experts said. "People do better when they're not grieving alone," Charney said.

Drawing on others

Carroll discovered the value of being surrounded by understanding peers after she lost her husband, who was commander of the Alaska Army National Guard.

In the months that followed, she gathered with some of the other wives whose husbands had been killed in the same plane crash. After a memorial service, they met for coffee and began sharing experiences. That turned into lunch, which turned into dinner, which lasted late into the evening.

"It was the opportunity to speak honestly, raw and real, without judgment." That was the birth of TAPS, which now helps thousands of survivors each year.

A key part of that aid is pairing new survivors with peer mentors. Among them is Noah Velazquez of Homestead, Florida. His older brother, Navy Petty Officer Third Class Joel Daniel Velazquez, was a submariner.

"He was a great brother," Noah recalled. "He was a great person," energetic and "always willing to help anyone he could."

After Joel died by suicide in 2017, Carroll and TAPS contacted Noah and his family to offer help.

"In the beginning, they pretty much provided me with everything I needed," he said. "They provided me with a shoulder to cry on when I wasn't having the best days," plus pamphlets, phone numbers and access to other people who had shared the experience of losing a sibling.

Knowing that someone shares your experience "makes it easier to talk to them, because they understand that loss," Noah said.

The family also drew strength and even inspiration from talking to Joel's former shipmates at military ceremonies that honored him. "We got to hear stories about him while he was stationed – things that we didn't know," Noah said.

One of those stories was about his selflessness. Joel had lent $150 to a shipmate in need without expecting it back. Later, Noah's father and uncle went out to eat together and found $150 on the ground, with a pin from a uniform. The family took it as "a sign, essentially that he was still watching over us," Noah said.

There is no clear path to getting through grief, Cozza said. "We've come to understand it's really like finding your way through a maze, or untangling wires."

Carroll said grief is a "lifelong journey" for people who have lost loved ones in the military. "For the families of the fallen – and for me – every day is Memorial Day. We carry their memory, their sacrifice and our love for them in everything we do every single day."

People who have suicidal thoughts should contact emergency services, go to the nearest emergency room, call or text 988 for the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline or contact local mental health crisis services.