Doctors shrugged off athlete's gasping, until one heart surgeon listened

By American Heart Association News

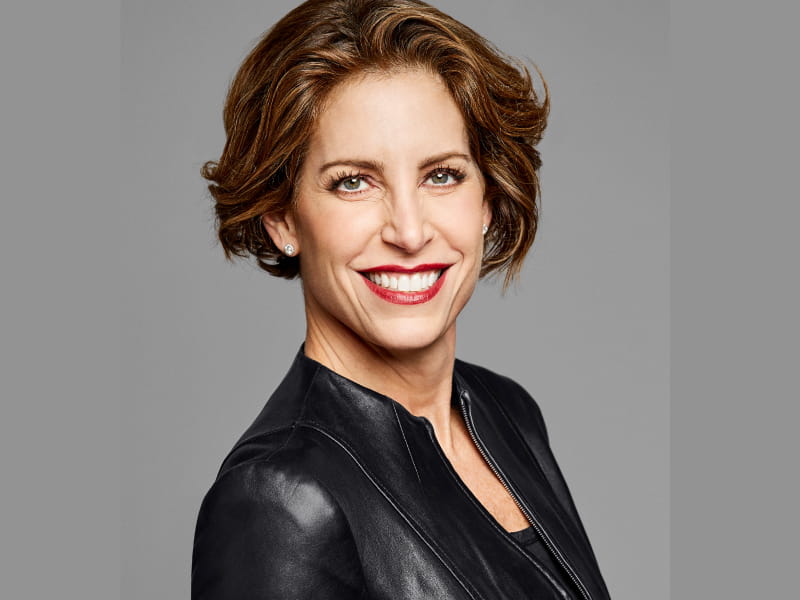

Back in her office after the New Year's holiday, Cat Oyler, then 45, struggled to catch her breath.

She felt like a heavy weight was sitting on her chest. She could take only a fraction of a normal breath, unable to expand her lungs or ribs.

Her breathing was so labored that her assistant sitting outside the office noticed and implored her to see a doctor immediately.

"I'm probably getting bronchitis and just need to go home and go to bed," Oyler told her assistant. "But first I want to finish this report."

Oyler was used to pushing through discomfort, especially where her breathing was concerned. Since she was a young girl, she'd never been able to run as fast as her peers, always becoming out of breath quicker than others.

Nonetheless, she became a lifelong athlete. Over the years, she played soccer, volleyball, softball and tennis, often winning her team's most valuable player award. She continued to play recreational sports as an adult and ran half-marathons.

Occasionally she told doctors about her trouble breathing; they always said she was fine. After all, look how fit she was.

On her most recent visit, she implored her doctor to find the source of her problem. He sent her to a pulmonologist. Tests came back normal.

This time, in her office, her breathing felt worse than ever. Only after her supervisor, himself a doctor, threatened to call an ambulance did Oyler accept a ride to the emergency room.

She had an electrocardiogram and echocardiogram. Although both showed slight abnormalities, the doctors weren't concerned because of her fitness level. She went home that night feeling back to normal.

When Oyler later told her parents about the incident, they reminded her she'd had a heart murmur as a young child, but they were told it had vanished by her fifth birthday.

A few days later, Oyler, who works with Johnson & Johnson in their global efforts against tuberculosis, mentioned her ER visit to some medical colleagues. They expressed immediate concern, with one doctor connecting her to Dr. Jorge Salazar, a cardiovascular surgeon who specializes in congenital heart defects in children and adults.

Talking to him was a revelation.

"I felt like Dr. Salazar was the first person who really believed me that something was wrong," she said.

He arranged for her to see a cardiologist in the Boston Adult Congenital Heart service at Boston Children's Hospital, where he was practicing at the time.

A cardiac MRI given at her first visit answered a lifetime of questions. It showed Oyler was born with an atrial septal defect, a hole in the wall that separates the top two chambers of the heart. This defect allows oxygen-rich blood to leak into the oxygen-poor blood chambers in the heart.

"Cat's heart was like an eight-cylinder engine firing on four cylinders without knowing it," Salazar said. "Cat was basically running a marathon seven days a week her whole life. What happened with her is that eventually her body was no longer able to compensate, and she started to exhibit heart failure."

Salazar, who is now at the McGovern Medical School in Houston, said Oyler is a perfect example of the 1 in 150 adults living with "silent" heart defects. The good news is, that number is falling rapidly with newborn detection practices, he said.

Once Oyler was properly diagnosed, doctors hoped the hole in her heart could be closed through a minimally invasive procedure. But after sending a device to her heart through a vein in her leg, doctors discovered the hole was the size of a large egg – too big for this method. She would need traditional surgery.

In May 2017, Salazar performed her open-heart surgery, closing the edges of the hole and suturing them shut.

The change in Oyler's breathing capacity was immediate. Just over two months later, she was back to running and better than ever. She could log a nine-minute mile with no training. Before, she'd trained hard to run a 10-minute mile.

Oyler hopes her story inspires people to advocate for their health because "no one knows you better than you." She also hopes people find inspiration in how she's putting her newfound energy to use – like spinning classes, which she'd avoided before. Last year, she traveled to Rwanda, hiking in high altitude to see the mountain gorillas.

In January 2019, exactly two years after her shortness of breath episode in her office, she was traveling in New Zealand and decided to celebrate by bungee jumping off the Kawarau Gorge bridge in Queenstown. She almost backed out, then she thought of her mantra since the surgery, which she uses to weed out unwelcome things in her life.

"Did I have open-heart surgery for this?" she asked herself. "Definitely yes."

Then she swan-dived.

Stories From the Heart chronicles the inspiring journeys of heart disease and stroke survivors, caregivers and advocates.

If you have questions or comments about this story, please email [email protected].